- Shop by:

- Department

- Accessories for the Musician

- Apparel

- Art Inspired by Music

- Childrens Gifts

- Christmas Ornaments and Bells

- Clocks

- Construction Kits

- Gifts - All Musical

- Gifts for Guitarists

- Gifts for Pianists

- Gifts for Saxophonists

- Gifts for Violinists

- Home and Garden

- Jewelry

- Karaoke and Recordings

- Mens Gifts

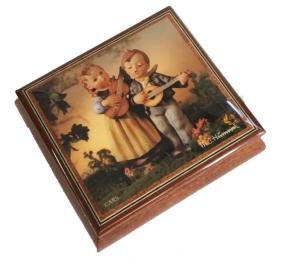

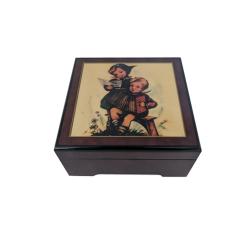

- Music Boxes

- Percussion

- Puzzles

- Sculptures

- Stay Safe - Masks & Sanitizer

- Watches

- Whistles

- Wind Chimes

- Occasion

- Manufacturer

- Acme Whistles

- Argent Creations

- Arte Felgurez

- Basic Spirit

- Bohme

- Cuddle Barn

- Enchantmints

- Ercolano

- Flights of Fancy

- Fridolin Maneville Musique (Hand Cranks)

- Gund

- House of Troy Music Lamps

- Karen Rossi

- Kingspoint Designs

- Kurt S. Adler

- M Cornell

- Mele and Company

- Menus and Music

- Mollard

- Mr Christmas

- Orpheus / Sankyo

- Porter Music Box Co, Inc.

- Porter Music Box CDs

- Reuge

- Rhythm Clocks

- Sadie Green Jewerly

- San Francisco Music Boxes

- Snowbabies by Enesco Dept 56

- Stadium Music Boxes

- Stained Glass Designs

- Timberkits

- Tolo Toys

- Unemployed Philosophers

- Unicorn Studio

- Vessel Jewelry

- Woodstock Chimes

- Yamada by Lefton

- Price

- Service

- Blog